The Magic Bullet Approach to AIDS Treatment: A look at the Brazilian program for universalization of antiretroviral drugs

By Tracee Saunders | December 04, 2012 6:57pm

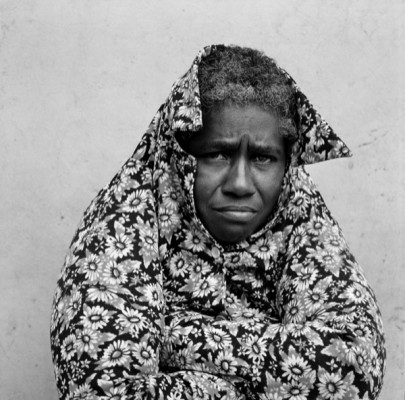

New recipient of Antiretroviral medication.

From Pajama Jeans to the Snuggie to the Magic Bullet, the home shopping network showcases a focus on trying to find simple solutions to complex problems. The pharmaceutical industry’s extreme growth over the last several decades has allowed this ideology to be applied to issues more serious than an over-crowded countertop. In the realm of global health, pharmaceutically focused model of care has emerged primarily as a result of the improved treatment plan for AIDS, the first major epidemic of the developing world.

João Biehl’s article “Pharmaceuticalization: AIDS Treatment and Global Health Politics” reviews the health care program in Brazil, the first developing country to provide universal access to antiretroviral drugs. Antiretroviral drugs (ARV’s) are the most common type of treatment for HIV/AIDS. Brazil’s program was launched in 1995; six years prior to the World Health Organization’s official policy shift from solely advocating prevention of the virus through education and group therapy to incorporating treatment. The widespread accessibility was made possible by an unexpected alliance of the activists, government reformists, development agencies, and perhaps most surprisingly, the profit-driven pharmaceutical suppliers.

Brazilian AIDS sufferer photographed by Biehl.

At first, the pharmaceutical companies manufacturing the antiretroviral drugs were trying to maximize profit and setting un-necessarily high prices. And the high prices made the drugs artificially unavailable to the poor. The acquired alliances, however, enabled the Brazillian government to reduce treatment costs by reverse-engineering the ARV drugs and promoting the production of generic options.

Reverse-engineering is the process used to create any variation of “generic” pharmaceutical product. Generic drug manufacturers incur fewer costs in creating the generic drug, as they do not have to cover the expense of drug discovery, or lengthy safety and efficacy trials. This means that generic manufacturers are able to maintain profitability while offering the drug at a much lower cost.

One of the primary concerns with the program Biehl addresses is the consistency and longevity of use the antiretroviral drugs require. Antiretroviral treatment keeps the amount of HIV in the body low to limit weakening of the immune system and to promote recovery of existent damage. To be beneficial, the medication must be taken every day for the remainder of a person’s life. Poor Brazilians are often characterized as noncompliant and untreatable, but this stigmatism only concretes their grim livelihood.

The “quick fix” nature of the antiretroviral drugs does not imply a negative in this case, however. It merely means that these chemical resources pose more potentially harmful risks than their talk-based therapeutic counterparts and that they require their users to be informed. The drugs should not replace the previously established group therapy sessions, but rather the drugs should supplement these sessions.

A group talk-therapy session for HIV/AIDS affected women in Kenya, where efforts are being made to establish a program similar to that in Brazil.

Further, the pharmaceutical innovations have not only allowed for unlikely partnerships, but they have also opened up new channels of communication and networking for the developing world. Of more than 40 million HIV positive people worldwide, 95 percent of them live in middle to low-income countries, significantly contributing to the low life expectancies in those countries. Several of the methods included in Brazil’s health program laid the groundwork for making collaborations with developed countries more plausible. By opening the flow of communication and access with developed countries, Brazil is able to take advantage of resources, like the antiretroviral drugs, that they would not otherwise be able to enjoy.

The Brazilian policy’s success provides proof that life-saving drugs can be incorporated into public policy despite lack of optimal pre-existing health infrastructure, which provides hope for other developing nations and the overall outlook for alleviating the AIDS pandemic.

Further Readings:

Social Innovation in Global Health: When People Come First

Between the Court and the Clinic: Lawsuits for Medicines and the Right to Health in Brazil

Bodies of Rights and Therapeutic Markets

HIV Drug Resistance Increasing In UK

Reference: Biehl, G. (2007). “Pharmaceuticalization: AIDS Treatment and Global Health Politics.” Anthropological Quarterly, 80(4), pp. 1083-1126.

Categorization: HIV/AIDS, Pharmacology, Global HealthFor more popular science writing, return from whence you came.